Hardcore Made Me Crazy – 102522

This is a newsletter by Christian Sager that comes out every other Tuesday. In it I attempt to make sense of the sensory chaos I experienced in the world. I try to sort that information along the model of Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs. This issue I write about health evaluation models, the word "crazy," and Jack Terricloth.

Physiological

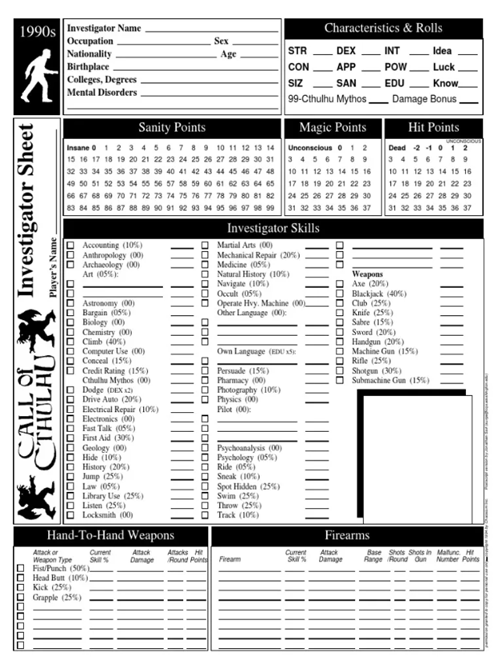

In order to save $17 a month on my health insurance, the state of Oregon asks that I submit a Health Evaluation Model survey once a year. The results that come back are not dissimilar from a character sheet in a role-playing game. You get an overall wellness score. Mine’s a 64 out of 100, delineated by a yellow, unfinished circle. Underneath, it ranks your health based on seven factors: heart, diabetes, cancer, obesity, nutrition, fitness, and mental. I score somewhere between a 78 and a 58 on them, with colored bar charts indicating whether I’m doing well or need to take caution about my health.

What follows is a breakdown of each factor and what experts recommend I do to raise my score. This is the gamification of society everyone in tech was excited about ten years ago. If I just get more experience points (by eating better, getting exercise, and balancing wellness) I can level up next year and raise my statistics. The ultimate goal of this particular game seems to be to live forever.

Which makes me wonder about the people who get a 100 out of 100 on their overall wellness score. Are they the equivalent of a Level 20 in Dungeons and Dragons or a level 150 in Elden Ring? Are they some kind of demi-god who’s fought every battle, defeated every “boss,” and discovered all the treasure? Or do they spend every waking moment thinking about LDL cholesterol, body mass index and blood sugar levels?

I want to live well and of course I want to avoid physical disease. But the simultaneous simplicity of this model and the herculean devotion it must take to play it well are both unappealing to me.

This was perfectly encapsulated by the section labeled “Happiness.” Based on my data it simply says: You: Sad, Goal: Happy.

Security

I don't know what it's like where you live, but Portland is a mess right now. Because of this I'm rooting for a measure designed to restructure our city government. There are a lot of residents against it. But I'm going to trust the process and that 20 expert volunteers can't be any worse at this than the current group of people running things.

Belonging

I remember working near Boston in 2002 and hearing an interview with Kurt Vonnegut and his son Mark on the radio. They were celebrating the reprinting of Mark’s book Eden Express, which detailed his major psychotic breakdown and recovery in the 1960s. I distinctly remember that during the interview, Kurt had a surprisingly irreverent take on both his son and his mother’s mental illnesses. I haven’t been able to locate that particular audio again, but around that same time the Vonneguts did an event at Harvard University, where Kurt said this to his son:

“Not only did we see you crack when you went crazy, we saw something beautiful when you got well. The recovery was worth it.”

As a mentally ill person who came from a family of mentally ill people, I remember being delighted by Vonnegut’s disrespect, not toward his son or mother, but toward the disease that had ravaged them.

At work last week I was told that we should avoid using words like “crazy” because they are ableist. I work in a School of Social Work, so I understand the context. Ableist language in the workplace and classroom is a common topic of both my colleagues’ teaching and their research. But something about that self-censorship didn't sit right with me and I thought about all the connotations that word holds for me.

Ariane Resnick’s “Types of Ableist Language and What to Say Instead” addresses this topic the simplest:

"Wow, that's crazy!" may not seem like a harmful statement, but if you think about someone with a mental health condition hearing that statement, it's easy to realize that it is. So instead of using one of those words, try outrageous, bananas, bizarre, amazing, intense, extreme, overwhelming, or wild.

Other articles I accessed through our university library argued that words like “crazy” are used to demean individuals, usually through microaggressions, where everyday interactions perpetuate inequalities against people from marginalized communities. One of these articles used the treatment of Greta Thunberg as an example of this in mass media, to the point that the American Psychiatric Association has advised journalists that “avoiding unwarranted and contemptuous terms can help reduce stigma around mental illness.” Another article argued this language also leads to internalized ableism, where a disable individual learns to hate themselves.

When I think about the word “crazy,” I have a deep, personal experience with the term. I have friends and family members who inflicted physical and emotional trauma — on me and others — because of their mental illness. Some of them were institutionalized. Some threatened suicide. They caused suffering. Some of them still do.

I think about how my family’s form of nurturing, compounded by their genetics, contributed to my own anxiety and depression. I remember my lived experience and how it took a lot of patience, medication and therapy to get to where I am now. I feel ownership over my craziness, because I surmounted how it debilitated me. I’ve reclaimed it. And I hope that other people have that opportunity as well.

The stigma seems to me to be in not naming it; in pretending it didn’t happen and it won’t happen again. We need more words, not less, so we have a more mature, complex way to talk about our tangled human minds and what they can lead us to do. In my experience, we’re often restricted from talking or writing about the things that matter the most, the problems that society doesn’t want to notice, much less solve.

In the hardcore punk music scene, “crazy” has its own unique connotations. Fans often use the word to describe bands — especially vocalists — when their performances reach the limits of what’s acceptable. Sometimes these are simply antics like thrashing around on stage or pretending to slit your own throat. Other times it’s more concrete. I’ve seen people cut themselves, blow balls of fire, or even force themselves to projectile vomit, just to impress an audience. That’s not even getting into Gwar territory, where musicians dressed like barbarian aliens hose the crowd down with gallons of mock urine, blood and semen.

I distinctly remember a conversation with a friend about David Yow of the Jesus Lizard along these lines. “People use the word ‘crazy’ to describe all these bands,” he said, “But this guy is legitimately insane.” Yow is legendarily known for doing weird shit, usually involving taking his clothes off and jumping into the crowd with his puh-noose out, as he calls it. The best story I’ve ever heard about him involved a guy going into a club’s bathroom, only to find Yow standing next to him at the urinal while he was still howling through a long-corded microphone over the band.

But band members aren’t the only ones who get in on the act. There’s a peculiar expression I’ve seen from audience members as well, especially when they’re fully immersed in their experience. They’ll grab the side of their head and shake back and forth, eyes rolling into the back of their head, mouth open, teeth clenched. It’s as if the music has driven them to lose all rationality, raising their id to the surface in a flurry of dementia. For a long time I’ve referred to this performance as “Hardcore made me crazy.”

As I get older I think of hardcore punk as a kind of lonely boys club. We identify with this music and these performances because they manifest something that’s going on inside of us, something that we don’t know how to express in our daily lives. The antics — both on stage and off — are a manifestation of this, almost a celebration of our collective alienation, anxiety and depression. In those spaces we can be crazy together and embrace the personality traits we can’t in public.

Esteem

I took one of my dogs for a walk on Saturday. We got about two blocks away from home before a car swerved off Fessenden and pulled up alongside us at the curb. I didn’t know if this person wanted directions or if something more sinister was up. Every time this happens I can’t help but think about Henry Rollins talking about living in L.A. in the 80s, where a car pulling alongside you either meant a) the cops, or b) a drive by shooting.

The vehicle’s window rolls down. In the passenger seat is a mopey-looking kid, probably in their early teens. Driving is a man who I presume to be the adolescent's father: tattoos, glasses, disheveled.

“Is that a World/Inferno sweatshirt?” he shouts to me.

I smile, realizing this is innocuous-punk-scene-comradery meets dad-talk. “Uh yeah, it is.”

Driving dad goes on to tell me about all his fond memories of World/Inferno. He’s a Sticks and Stones fan and he once saw Jack Terricloth fill a jack o’ lantern with leaves and set it on fire on stage. I nod; I’ve also witnessed these famed pyrotechnics, going back twenty plus years now.

And just as quickly, they drove away, the teen saying nothing the entire time. I’m thinking about how amusing that is and how Jack himself would have appreciated the humor in it. “My dad is so embarrassing… he told a total stranger how much he loves some old band whose singer is dead and used to vandalize shit on stage.” 🙄

Jack’s been gone for about a year-and-a-half now. A non-profit foundation started and is holding a tribute concert for him next week. I’ve been thinking about him a lot lately, probably because Halloween is coming. When he died I said he was who I wanted to be when I grew up. And it’s true; I had an imaginary idea of him — a parasocial relationship. But I also think about how different we are, me and that parasocial Jack. Every time I read about black bloc protests I imagine him cheering them on, while I shake my head, wondering how we’re going to move forward after they're done venting.

I don’t think those differences would preclude us from getting along, at least for one night in the dark corner of some bar. So on Halloween I’ll raise a glass in his honor and toast a brave men who lived his life just as he would have it.

Self Fulfillment

Been working more on the novella, plowing through Act 2. I'd love to start releasing it in chapters next year. When I told a committee of colleagues this week that I'm working on a horror book they seemed genuinely surprised. I must keep the different facets of my identity more under wraps than I think I do.