011723 – The Death of the Nineties

This is a newsletter by Christian Sager that comes out every other Tuesday. In it I attempt to make sense of the chaos I experience in the world. I try to sort that information along the model of Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs. This issue I write about disturbing behavior in Portland, how the band Unwound makes me feel, and getting angry about Twitter in higher education.

Physiological

Went to the dentist this week. It reminded me of the time the frontman of a band I was friendly with told me that dentistry was a capitalist conspiracy. He believed the entire branch of medicine was unnecessary.

Safety

It’s been a bit of a disturbing two weeks here in Portland. We’ve had three incidents that raise the ol' situational awareness when we’re talking about Maslow’s “security of the body.”

- A woman pushed a three-year-old onto the train tracks at a public transit station.

- Another person attacked a 78-year-old on a different train platform, claiming that they thought the victim was a robot. They chewed his ear off until his skull was visible.

- Another person burned down a 117-year-old church, a few blocks from my day job. They claim voices in their head told them to do it.

I can tell when local news is click-bait fear-mongering our community over crime. This seems like something else. People are genuinely shocked and there’s no remedy in sight for our city’s homelessness and addiction struggles.

Belonging

I’m usually of the opinion that writing about the music you love is alienating for your readers. In fact, most music journalism doesn’t work for me. Despite that, I’m going to spend some time here writing about a band called Unwound. My goal isn’t to review their music or try to convince you to listen to it. What I'm going to attempt is to capture the way Unwound makes me feel, and how that feeling has changed over 30 years.

Here’s an example of why I don’t care for music writing:

“Unwound played a sharply dissonant and angular style that made use of unusual guitar tones, and garnered attention locally for their relentless touring schedules, favour towards "all ages" venues and their strong DIY ethics.”

That sentence (from Unwound’s Wikipedia entry) does nothing to describe the music for a person who hasn’t heard it. I’m about to cite another piece that at least went a step further at getting to the core of how Unwound makes me feel.

Jason Heller wrote about them for the AV Club in 2013, with an article titled “Why Unwound is the best band of the ’90s.” Heller’s argument is that Unwound (whose discography ran from 1991 – 2001) captured the spirit of the 1990s, but that spirit died on September 11, 2001. Effectively, so did Unwound.

“But in a decade where most bands were either stridently earnest or stridently ironic, Unwound wasn’t stridently anything. It was only itself. In one sense Unwound was the quietest band of the ’90s, skulking around like a nerdy terror cell. In another sense it was the loudest, sculpting raw noise into contorted visions of inner turmoil and frustration… The band existed apart from, yet roughly parallel to, the primary streams of ’90s rock—avatars of an alternate history of the decade, one where pop didn’t win again, as it had after every other counterculture movement. To Unwound, the ideals ushered in at the start of the alternative revolution actually mattered and were honored. There are hooks galore in Unwound songs, but the listener has to work for them. And they’re more dimensional, emotional, and rewarding because of it.”

I think there’s something to Heller's argument. If “The Dream of the Nineties” was alive in Portland by 2011 for Portlandia, then that dream must have crash-landed near here in 2001 when Unwound returned from their Leave Turn Inside You tour. The story goes that the tour was already miserable before it came to a screeching halt the day of the 9/11 attacks, when they were supposed to play at The Middle East club in Cambridge, Massachusetts. They went back to Olympia, Washington and disbanded a few months later.

I buy into Heller’s theory, that Unwound’s trajectory matched the evolution of independent music during the decade they were active. When you go back and trace that trajectory, you get a sort of cultural map that points in the direction of what Americans mean when we think about the zeitgeist of the 1990s.

When I overlay that map on top of the timeline of my life I recognize two things: I wasn’t ready yet for what Unwound offered. But somehow they’re still integral to my identity.

Unwound guitarist and vocalist Justin Trosper has said:

“I think we usually approached all of our records with a slightly apocalyptic approach. My state of mind in the '90s was that way. I always felt like the end was near.”

That statement sounds like he's describing me, except that my apocalyptic state-of-mind didn’t end with the 90s. Escaping that mindset certainly wasn’t helped by the events of the year 2020. The death of Unwound bassist Vern Rumsey was among the tragedies of that year.

But as I’m writing this, Unwound are planning to perform a reunion tour, with bassist Jared Warren filling in for Rumsey. I have a ticket for the fifth show in that journey and my anticipation has built for months now.

Let me tell you why.

When I was first discovering punk rock in high school I received a catalog for the Kill Rock Stars record label in the mail. Designed like a photocopied fanzine, that catalog was a window into a mysterious world I wasn’t part of yet, with strange band names like “Witchy Poo” and “Universal Order of Armageddon.” It had typewritten, cut up technique text purposefully misaligned atop high contrast scans of flyers, album covers and photographs I didn’t understand. This is where I first heard about Unwound, in an entry for their debut album Fake Train. Here’s what it said:

“FAKEtrain.space is the place. Mysterytrain. Atrain. Night train. Coltrane. Train keeparolling. Nighttime. Spacetrain. Rocket#9nxtstopEARTHnyquilrockin the 90’s.”

None of this made any sense to me. I had no points of reference for the cultural touchstones the catalog invoked. It seemed like a secret message from another planet. That planet was the Pacific Northwest of America.

Today, over 30 years later, I still associate that letter-sized catalog with the region, even after I’ve lived here for close to five years now. I imagined it was gloom and rain and rusty dilapidated structures. I wasn't far off. The catalog entry for Unwound’s second seven-inch said, “It’s the gloom you can only get in youth.” To me, he PNW was all do-it-yourself chaos, feminist dissidents and enigmatic riddles that I needed to decipher.

Two years before she hit us with that “Dream of the Nineties” song, Carrie Brownstein wrote about Unwound for NPR in 2009 and said:

“Unwound synthesized all that was exciting about Olympia and music in the Pacific Northwest. Its music dark and often experimental; it had pop riffs that grew out of murkiness only to disappear again; its songs gave you glimmers of light but never flooded you with sun; there was angst but not brutality; it possessed an uneven wilderness, which is all you'd ever want from music, something unexpected emerging from what we already know.”

What she writes there captures how I felt about the band before I’d ever even heard them. The listening came a few months later, when my girlfriend played me her vinyl copy of the Kill Rock Stars compilation album. Finally, this was my opportunity to hear these bands that I’d only imagined until then!

But when the record came to Unwound’s track, “You Speak Jealousy,” I was deflated. At the time I couldn’t articulate why. But listening to it again today, it's not a particularly memorable song. Sure, it makes up for a lack of talent with energy. But even though they were trying to do something different, I didn’t really like Unwound when I first heard them.

Today I recognize something else about the song. It sounds like dozens of bands I saw play shows in basements throughout the late 90s, including some of my own. What I was bored by in early 1995 would go on to be the same kind of novice noise rock I myself produced from 1996 – 2002.

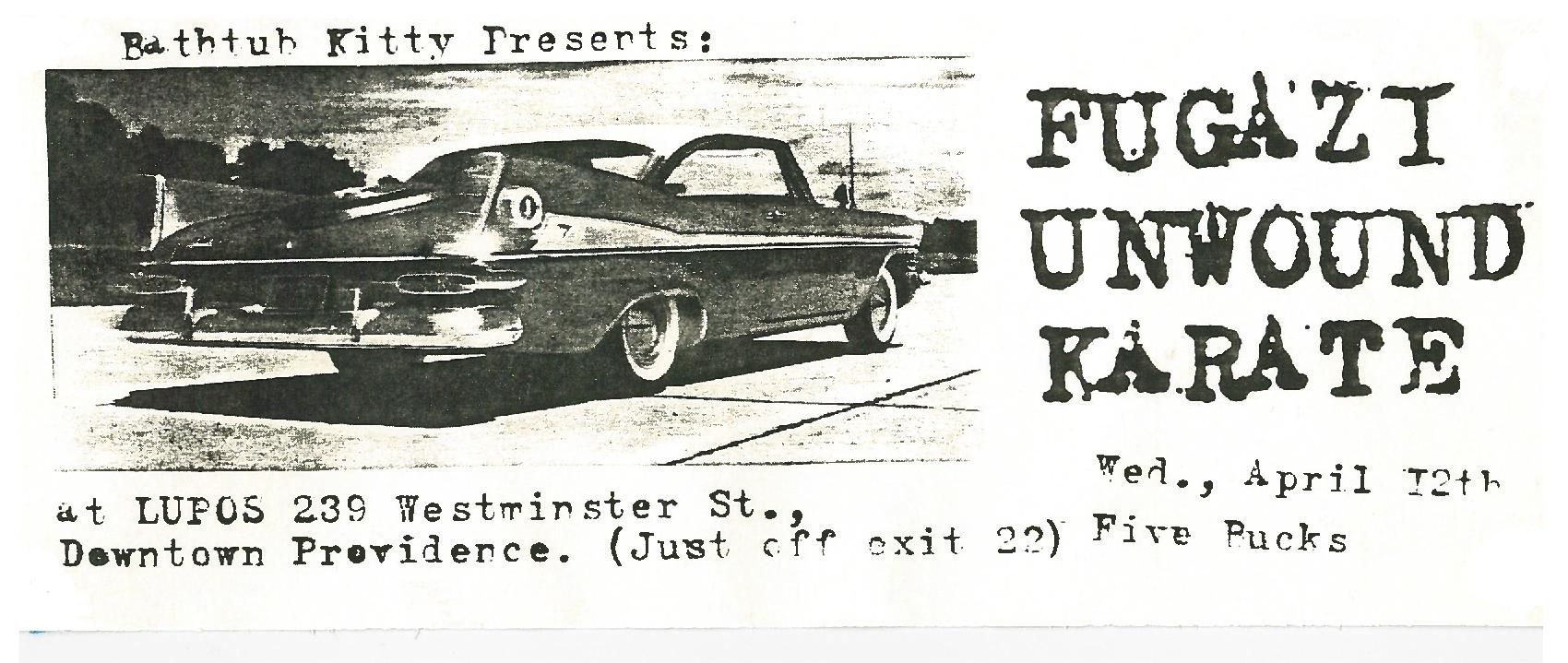

The musical similarity is probably because we were all trying to imitate Fugazi. On April 8th of 1995 — a month before I would graduate high school — I drove up to Portland, Maine with a car load of friends to see those Washington D.C. legends in a gymnasium on the campus of the University of Southern Maine. Unwound opened.

Despite being in the front row, I only vaguely remember their set. That’s because a few songs into the performance, some jackass stage-dived into the crowd and kicked me right in the face on the way down. One of my contact lenses popped out and for the rest of the show I had monocular vision, my face throbbing from the impact. So my recall of the moment isn’t great. But when Heller writes about his own 1995 experience with the band it is pretty close to what I recall:

“Sickly and withdrawn, the members of Unwound sulked in the corner like outsiders at their own party… If anyone was sweating during Unwound’s moody, mathy spasms of feedback-shrouded mystique, it was out of nervousness.”

They were skinny and pale, just like we were. But they wore long-sleeve button downs on stage. Rumsey let a cigarette hang from his mouth aimlessly. Not long afterward I’d start to cut my hair in the same style as Trosper.

In another piece about Unwound, Emmeline Mead writes:

“I think that after you live in this area (the Pacific Northwest) for awhile, enough rainwater seeps into your brain that moody, melodic dissonance is the only thing that makes sense.”

And again, this matched my experience. Seacoast New Hampshire has a similar ambience, but instead of constant rain it gets shovels full of snow dumped on it as well. By the time I got to college, “moody, melodic dissonance” was about all I listened to.

Not long after, someone handed me my first Unwound album.

I was a college radio deejay at WUNH for about six months before the station’s production manager interrupted my 2–6 am set with dead air because I played GG Allin and he thought the Federal Communications Commission were listening. Before I quit the station however, I got a free copy of Unwound’s The Future of What.

They’d definitely leveled-up in my self-righteous, teenage opinion. The cover art portrayed a drawing of Russian constructivist architecture. The guitarist used sustain to make sounds like airplanes falling out of the sky. The vocals were mumbled, too low in the mix, with vague, free-association lyrics. This was definitely more my thing than that Kill Rock Stars song I'd heard months before.

And then… I didn’t really listen to them again for another six years. No particular reason; their path and mine just didn’t align. While I was playing in my own bands, uncovering my identity, touring the north east and xeroxing my own artsy flyers, they put out three more great albums and toured endlessly.

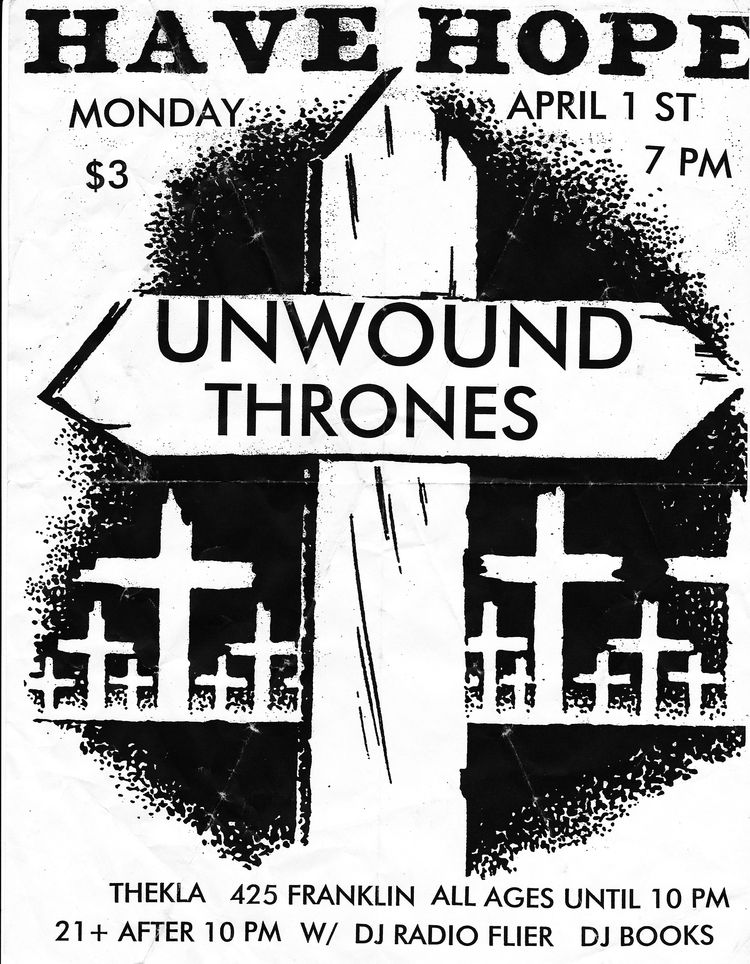

But on September 9, 2001, a friend invited me out to Amherst, Massachusetts, where Unwound were playing at a college student lounge with Mecca Normal and Thrones, the one-man bass monster we were currently obsessing over. A different girlfriend had recently broken up with me, but for some reason we drove out there together. I still conflate the whole experience with that confusing period between devotion and animosity.

This was the infamous, last Unwound tour, only two days before those planes hit the World Trade Center, the Pentagon, and a field in Stonycreek Township, Pennsylvania. It was the last show Unwound played before that awful event. Months later they’d call it quits. None of us had any idea.

Remember, this tour was in support of Leaves Turn Inside You, now critically-acclaimed, with an influential legacy. It is one of my all-time favorite albums. I don’t think I’d heard it yet, but here’s a good description of how it makes me feel now, from Evan Ryetlewski in Pitchfork. Although, this is another example of a music review that does nothing to describe the music for a person who hasn’t already heard it:

“The whole record exists in a permanent November, condemned to those waning days of fall when all the color has been drained from the skyline, and all that’s left are barren trees and an isolating chill.”

What I do remember from watching Unwound perform that night was a dawning comprehension. They were influenced by the same music I was. Even though I hadn’t listened to them in years, I played guitar like Justin Trosper. Hell, I even dressed like him. They were like me, just a few years older and from the cryptic other side of the country. I didn’t realize it until that very moment, but Unwound was the band I wanted to be in.

And then they broke up.

Not long after, I left my last band and haven’t seriously played music since.

Fast forward to August 6, 2020, when I learned that Vern Rumsey died. By all accounts he continued relapsing into alcoholism, even after a liver failure health crisis. I never knew him, but I knew dozens of guys like him. I thought about them that nightmare summer, when there were violent protests every night, a pandemic ran rampant, wildfire smoke truly trapped us indoors, and I was unemployed in the middle of an economic collapse.

The Unwound reunion is now three weeks away. Two days afterward I’m going to see Thrones. I expect there will be a lot of emotion condensed into those sets. It will dredge up frustration, disappointment, separation and the embarrassing confession that part of my identity is based on an imitation of someone else’s. That apocalyptic state-of-mind will get invoked. But now we’ve experienced an era far more like an end-of-the-world than we could have ever imagined, long after a decade-long-gone ended in a tremendous, violent crash that changed us forever.

And the secret message that arrived in my mailbox all those years ago has long since been decoded. That mysterious enigma is where I live now: damp, skeletal trees covered in moss, methane hanging in the air around abandoned warehouses, empty storefronts and a crumbling infrastructure waiting to be reclaimed with neon signs that barely keep the perpetual night at bay. This is where I live.

Esteem

A few weeks ago, a communications colleague of mine expressed concern about Twitter during a business meeting. They invoked the company’s unjustified termination of employees, the disinformation spread by Musk, the growth of its hate speech, its banning of journalists, and the reinstated accounts of many extremists. Their argument was that our organization should consider abandoning Twitter as a marketing platform, because this behavior runs contrary to our stated values as a higher education institution.

We recently had a follow-up meeting where we were told the following in response:

- We should stay on Twitter as an institution, because it’s a platform where many academics still communicate.

- We should stay on Twitter because our institution needs to have a corporate mindset instead of an activist one.

- We should stay on Twitter because if we left, it would set us up for criticism for all the other ethically-dubious companies we have partnerships with.

- We should stay on Twitter because the only organizations who can afford to leave Twitter are the ones who already don’t have enough reach there to suffer any repercussions.

- We should stay on Twitter because leaving would be performative.

- We should stay on Twitter so our organization isn’t impersonated there by bad actors.

- We should stay on Twitter because it is still the best platform for trend-watching and we need to stay on top of the trends that interest Generation Z.

These are all arguments made with logic in mind, though I doubt many of them would hold up to a traditional claim/data/warrant analysis. I’m not going to break them down here.

What the overall argument lacked was any attempt to use other modes of persuasion, namely ethos (the quality of the speakers’ character) and pathos (the emotional connection). The closest thing we got to an ethos was when the speaker said, “I’ve been on Twitter for almost ten years” as a kind of badge of honor for telling us what to do.

I found this experience... triggering. A red hot anger rose up from the tips of my toes to the top of my skull. For a week afterward I wondered why. What was it about this response that irritated me so much?

As I unpacked it, I realized all of my reasons fell under the integrity and compassion the speaker left out of their response. The tone was condescending; as if we were being disciplined for daring to consider the moral implications of our business decisions. That was patronizing.

It also reminded me of a string of bad experiences I’ve had with similar people in the digital media world. At one of my wife’s former workplaces they referred to this kind of desperate tech influencer as a “digital douchebag.”

I found it frustrating that a social justice oriented organization would tell its employees to kneel before The Stacks, because that submission is an inevitable conclusion of modern capitalism. This showed a lack of integrity on both an individual and an institutional level.

Finally, the colleague who originally expressed concerns about Twitter wasn’t even there. She couldn’t defend herself. The other attendees had no response, staring forward silently into their Zoom grid.

I asked my wife afterward, “Do you think they could tell how angry I was? I was on mute.”

She responded, “You don’t exactly have the best poker face dear.”

The whole experience made me miss my friend and former colleague Cliff Landis. A decade ago we were able to puzzle over these issues together, making arguments for ethical social media while staying technologically literate. I’ve been reading a lot of related Cory Doctorow non-fiction lately, namely his Locus magazine essay on “social quitting” and his follow-up post expanding on it. I wonder what the Cliffs of the world make of that.

I recently decided to attend South by Southwest again this year. Will there be anyone there considering the repercussions of our social media apathy? Or will it be hundreds of venture capital tech bros shilling cryptocurrency and the metaverse? When I’ve gone to this event before it was for the insights of intellectuals like Bruce Sterling or Jessamyn West. Is there even a place for that kind of critical thinking there anymore?

Raw Signal Group recently published a newsletter about Shopify’s recent anti-meeting stance that I enjoyed. In it, they said:

“As people who spend a lot of time on startup management, there's often a lot of noise. Tech execs tend to be a loud, chest-thumpy bunch. The business press corps often has limited business experience and less management experience. They write breathlessly and uncritically, unable to distinguish smart policy from tech-culture-war-garbage.”

That resonated with me, especially after the Twitter dress down. Maybe I’m not the only one out here, gnashing my teeth every time some sycophant grovels for the table crumbs that Zuckerberg or Musk leave behind on the floor.

Then I read that the people who run Mastodon rejected more than five investment offers from venture capital firms. And I thought, “Maybe there is some hope that one day we’ll treat social media like a public utility and not like a turn-of-the-century abattoir.” So I signed up.

I’m still experimenting with it, but you can follow me there at: https://mstdn.social/@christiansager

Self-Actualization

Made a breakthrough with the novel this week when I added a scene featuring ASMR. I'm finally able to make use of the research I did when I wrote the script to this video performed by the amazing Cristen Conger.

Resilient Gratitude

- Nona the Ninth

- Wyrd Science

- Introducing a six-year old to Transformers toys